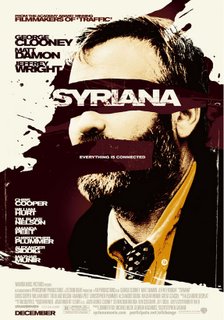

I have mixed, but mostly good, feelings about this brutally powerful film by first-time director Stephen Gaghan. Like he did in Traffic (for which Gaghan won the Oscar for best screenplay) Syriana weaves what are initially unconnected narrative strands into a dense web of geopolitical polemic. Whereas Traffic was a pessimistic lecture on the futility of the drug war, Syriana's main character is oil itself, depicted near-mythically as a demonic, corrupting force seizing the will of the great powers of this earth. Picture the greedy, panicked eyes of the characters in The Lord of the Rings as they fall under the ring's spell. Syriana sees everyone as a potential Gollum, susceptible to a morally warping desire. There are other themes, such as the global ripple effect of even seemingly insignificant choices, and a more subtle insinuation that those who profit from oil, whether governments or businesses, actually prefer, and will in some cases even encourage, global instability – the conflict drives oil prices up.

I sensed that the creators were attempting to redresss an imbalance, rather than be taken as a measured picture of the way things are. Accordingly, I had the uncomfortable sense of being preached to that comes from anything mixing so much agenda in with its artistry. But it attacks the self-centered limits of the western worldview with gentle empathy, rather than bile, and I found the light touch affecting. What it does best is give someone like me, weaned in the comparatively prosperous west, only the slightest glimpse into the humiliation and frustration that an average person, suffering in one of the backwards places on the other side of the world, feels when a foreign power imposes itself in the name of commerce. The greatest achievement here, the thing that stayed with me long after, was its tender depiction of Pakistani teenage boys who are simply not like us. The differences were subtle – their jokes and pastimes had a sense of filtered westernization – but there was a humble otherness to it that rang true. Usually, when foreigners or minorities are portrayed for sympathetic reasons, it’s done in a way to make them seem more, not less, white. But these kids were believable in their simple, adolescent awkwardness. And that made their radicalization both convincing and heartbreaking to watch.

In fact, most of Syriana's major Arab and Middle Eastern characters – from Hezbollah leaders to Saudi royalty – are portrayed neutrally to positively. That is, above all, what makes the film unique, if overly romanticized. (Its other rhetorical storylines – a CIA agent sold out by his own, oil companies manipulating politicians, etc. – though engaging, lack newness.) It's also what makes it fishy as a thesis. Yes, it's bitterly cynical but to me it's not cynical enough. It's hard to accept this level of indignation at the covert sins of a country like the U.S. without a comparable or harsher reaction to the overt brutality, misogyny or chronic opression of the world's Iraqs and Saudi Arabias. In this sense, Syriana is a little too reactionary for me: events in a terrorist training camp are lit warmly, like an idyllic Eden; Hezbollah is portrayed as benevolent and gracious; while any western players, from lawyers, to financial advisors, to politicians, are varieties of thieving devils. It's as if the filmmakers had an over abundance of empathy; just not for anybody on this side of power divide.

Sadly, the confusing format of the movie –– not its politics –– is probably going to be the most divisive thing about Syriana, and will likely dampen the effect of its ideas. The film's unique construction –– watching it is like having your mind force fed a gushing stream of information faster than it could possibly swallow –– is both frustrating and admirable. Though told linearly, it's edited at a super-quick pace; scenes are usually truncated. The scope of this movie is humungous –– a perspective ranging from the highest seats of influence to the poorest and most powerless – yet the effect is of a statement needing a context. Yet it doesn’t come off as an arbitrary choice and it seems deliberate that it is impossible to completely comprehend on first viewing. The result is an overwhelming and, at times, maddening style that is awfully impressionistic for a work that is essentially NPR-turned-feature-film. And therein lies the conflict for me the viewer. On the one hand, it gives the sense of someone bluffing; alluding to more knowledge then they really have. On the other, it forced me to watch the film not as a series of expositions, but as a sequence of emotions. That's something fresh. The acting, direction and score are so exquisite that the tonal thrust of everything you see is always articulated. Just not in a cerebral way. I saw it as a parable about not getting so caught up in the enormous details of current events that we forget to see the human picture.

From the original score by Alexandre Desplat:

Driving in Geneva

Something Really Cool